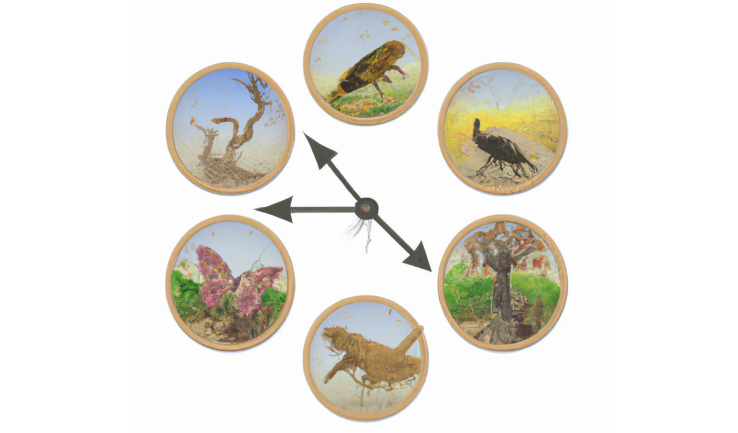

We have long been interested in understanding how populations adapt to both fixed and changing environments.

One important factor that affects adaptation is the movement of individuals between groups and subpopulations, or dispersal.

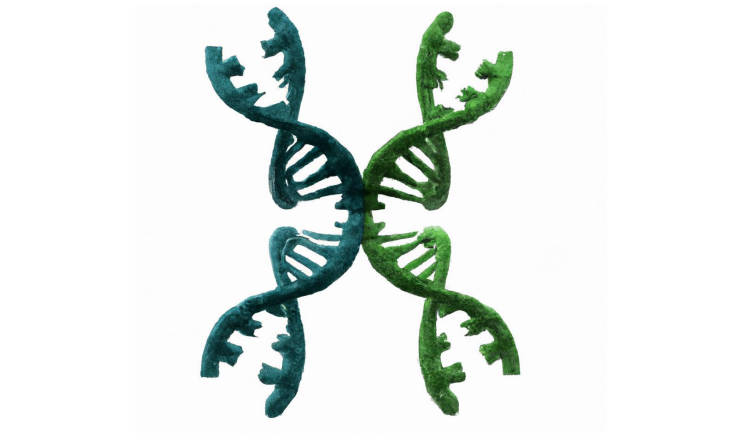

In this study, we use mathematical models and computer simulations to investigate how limited dispersal affects the process of adaptation.

We found that, contrary to previous findings, limited dispersal can actually speed up adaptation in some cases.

Specifically, when a beneficial trait is controlled by a recessive gene, limited dispersal can increase the frequency of homozygous individuals, which in turn exposes the recessive gene to selection and speeds up the process of adaptation.

However, this effect only occurs when dispersal is not too limited, otherwise the inflation of effective population size caused by dispersal limtation outcompetes any other possible effect of selection.

We also found that the mode of adaptation (i.e. “hard” or “soft” sweeps) can affect the consequences of dispersal limitation and the signatures that those sweeps cause in genomes.

Overall, our study highlights the complex interplay between dispersal, selection, and genetic drift in the process of adaptation.

By shedding light on these factors, we hope to contribute to our understanding of how species respond to changing environments, and how we can better conserve biodiversity in the face of global change.

The first publication of this work with my PhD supervisor, Charles Mullon, is available on Genetics.